Long a fixture of Austin activist circles, Alice Embree reflects in her new memoir on decades of involvement in radical organizing. Her experiences in the 60s and 70s as a member of Students for Democratic Society, an anti-war and civil rights activist, and an editor of the underground zine The Rag offer important lessons for today’s radicals.

By Adam S.

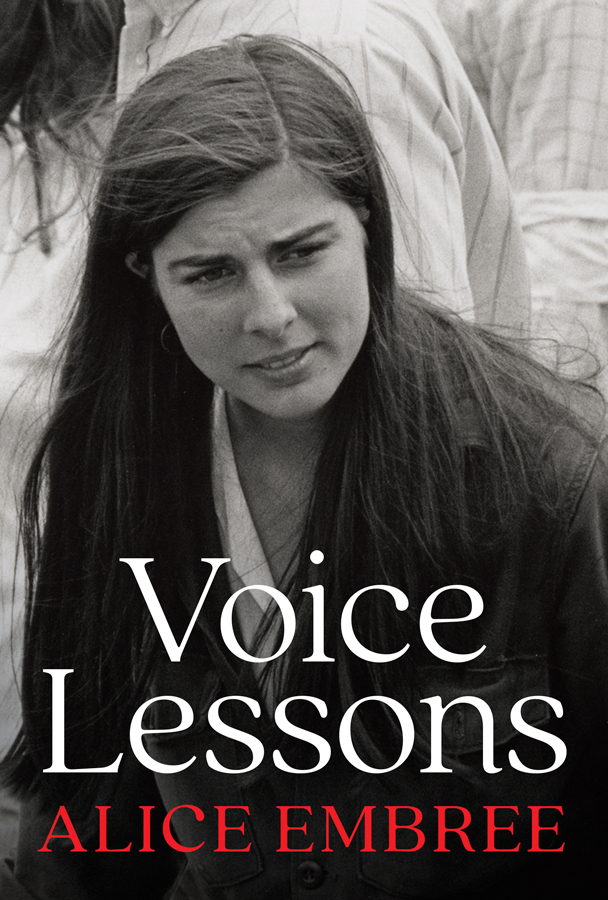

Review of Voice Lessons by Alice Embree (Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas Press, 2021).

Alice Embree’s memoir Voice Lessons weaves stories of inner and societal change to tell the story of a radical awakening in small town Austin, and paints a carefully considered portrait of a life in and of movements. The book begins with a sketch of a childhood in a much smaller, much more segregated Austin: “Fewer than 160,000 lived in Austin in 1955, and the thundering roars of jet-propelled commercial flights were far in the distant future,” she writes. Behavioral observation is a skill Embree learns early, and not infrequently what she sees is acquiescence to oppression. In the ‘50s topics like menstruation and birth control were taboo, and she also watches as the adults in her immediate family trip around the subject of her mother’s cancer as if the disease was a personal failing.

A telling incident occurs in 1961 when Embree is on a school trip as part of the “Red Jackets,” the Austin High drill squad. The Red Jackets were integrated, and after being turned away from one restaurant, at the next “a waitress came over, addressing Glodine [a Black student] in the sweetest voice, ‘I’m sorry, honey, we just can’t serve you here.’” Embree recalls, “I wasn’t afraid to speak up, but I expected others to respond, to get up as well. No one else did. The adult sponsors didn’t intervene. They didn’t follow us outside…it was the silence that shocked me.” Breaking up the silence becomes a passion for Embree at The University of Texas, where she joins the Students for a Democratic Society, picketing and sitting in at segregated lunch counters. She develops her voice by working as a typist and editorial assistant (charmingly referred to as a “Shitteworker”) at the countercultural ‘zine The Rag, and then as a writer full stop.

Many memoirs by authors radicalized in the sixties use the decade as the central ballast for their stories, but for Embree that time serves as a springboard first into women’s liberation and then more broadly into ‘intersectionality.’ The process is gradual, but it all leads back to one moment, a phone call that Embree says “changed my life.” After moving to New York with her then-partner to launch another countercultural magazine called The Rat, Embree comes to observe and realize that her partner’s progressiveness only extended to where his comfort zone ended—and after that was a politics indistinguishable from mainstream male chauvinism and racism—spurred Embree to search for a truly inclusive movement. Suddenly, “the personal became wrenchingly political,” as she puts it, and “an unfamiliar rage, rooted in a thousand dismissals, came to a rolling boil.”

Embree eventually leaves her partner and becomes fully ensconced in this new activism back in Texas, which involved not just a feminist awakening at The Rag, but the formation of the Austin Women’s Center and a women’s birth control hotline, which Embree says addressed “two issues women faced: access to birth control and access to safe, legal abortions.” Embree stepped into more leadership roles. She became an organizer of the Texas Media Conference and in her off time placed a hex on the LBJ library with her sisters in WITCH (the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell).

Feminism was Embree’s driving force in the seventies, and she formed or joined grassroots organizations like the Austin Women Workers, the Austin Women’s Health Organization, and more. And while in the sixties Embree’s interest in democracy abroad led to her getting involved with the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA), in the following decade her international advocacy expanded, especially after Chilean president Salvador Allende was deposed in a military junta in 1973. Embree and other Austin activists responded first by crashing CIA director William Colby’s speech at the University of Texas, and later creating The Austin Committee for Human Rights in Chile, active from 1977 until democracy was restored in that country in 1989.

One potential pitfall for memoirists is the tendency to embellish potential or personality, which Embree avoids through honest appraisal. “We were like butterflies, with the gunk of the chrysalis still stuck to our wings, the legacy of ‘50s expectations shrouding our vision,” she says, and later writes: “Our concept of revolutionary change was, to put it mildly, naive.” Embree is one of many activist memorists to reach a similar conclusion, but what sets her apart is optimism. “The energy level of younger activists, new to the struggle, is both exhilarating and exhausting,” she states toward the end of her book, and tells me via email that she was “elated” when leftist Gabriel Boric won the Chilean presidential election. For her part, Embree expresses that “I hope I bring a sense of staying power, a reminder not that we did things better in the ‘60s and ‘70s but that movements in our younger years changed the trajectory of our lives, not for a decade or two but for a lifetime.” Activists lucky enough to have met Embree can attest to her knowledge and strong example, to say nothing of her staying power. For those who haven’t had the pleasure, Voice Lessons is an excellent introduction.

We want to hear from you. Do you have a workplace story or editorial you’d like to share with us? Email us at redfault@austindsa.org!