In our increasingly atomized and hollowed out society, it can be hard to imagine a robust working-class culture. In fact, there is a long history of working-class people banding together in their own independent organizations to fight for change. If we hope to challenge rising unaffordability in Austin, we will have to do the same.

By Jake J.

One of life’s simple pleasures is grabbing a beer after work with some of your fellow workers. It’s a nice way to get closer with your coworkers, talk about the shift, and relieve the pressure we face on the job. It’s also a great time to talk politics or, better yet, organize for action in the workplace without the boss looking over your shoulder. Like everything else in Austin, it’s also becoming more expensive.

The reason is no secret. Real estate capital and tech companies are conquering our city and pushing out the things that made it a nice place to live in the first place. Corner beer joints and dive bars have been pressed in recent years by skyrocketing land values and rent. Some have jacked up prices in an attempt to keep up with the increasing cost of doing business. For many, the pandemic was the straw that broke the camel’s back. As Austin institutions are liquidated, cocktail bars and craft beer gardens spring up in their place, serving overpriced drinks to wealthy condo denizens.

The rising price of booze is just one ever-present symptom of a pervasive problem in our city: the commodification of culture in all forms. The people who made this city a cultural capital—painters, poets, small-time filmmakers, and musicians—can’t afford to live here anymore. Low-wage workers in food service, retail, construction, education, transport, logistics, and healthcare find themselves in a city that is looking more and more like a playground for the rich. In an increasingly expensive city, it’s important to value and patronize the vestiges of old Austin, purveyors of cheap beer included.

Ultimately, Austin will continue down the path toward unaffordability unless we do something about it. Only an institutional left and a robust working-class culture can change things for the better. An institutional left would contest the power of capital in our city on every terrain. It will operate under the guiding principle of independence from the rotten two-party system, aiming to bring working-class people together in their own political groupings, independent of capitalist influence. Expanding on our wins at the ballot box in recent years, the left could target local and state offices, with the goals of improving the lives of working people, increasing protections for renters, ending giveaways to corporations, increasing public investment in local cultural institutions, building public housing and more.

A necessary component of independent political organizing will be creating a working-class culture. Working people have interests distinct and opposed to capitalists, making it necessary for us to have our own institutions, publications, clubs, and hangouts. This is not without precedent, but certainly seems foreign to us in our increasingly hollowed out society. In the late 19th century, German socialists operated thousands of bars across the German Empire, which served as inexpensive meeting spots and homes for social outings. Alongside beer drinking, they also organized their own singing societies, hiking clubs, sports teams, and study groups. This working-class counterculture involved hundreds of thousands of workers and was an important component of building the party.

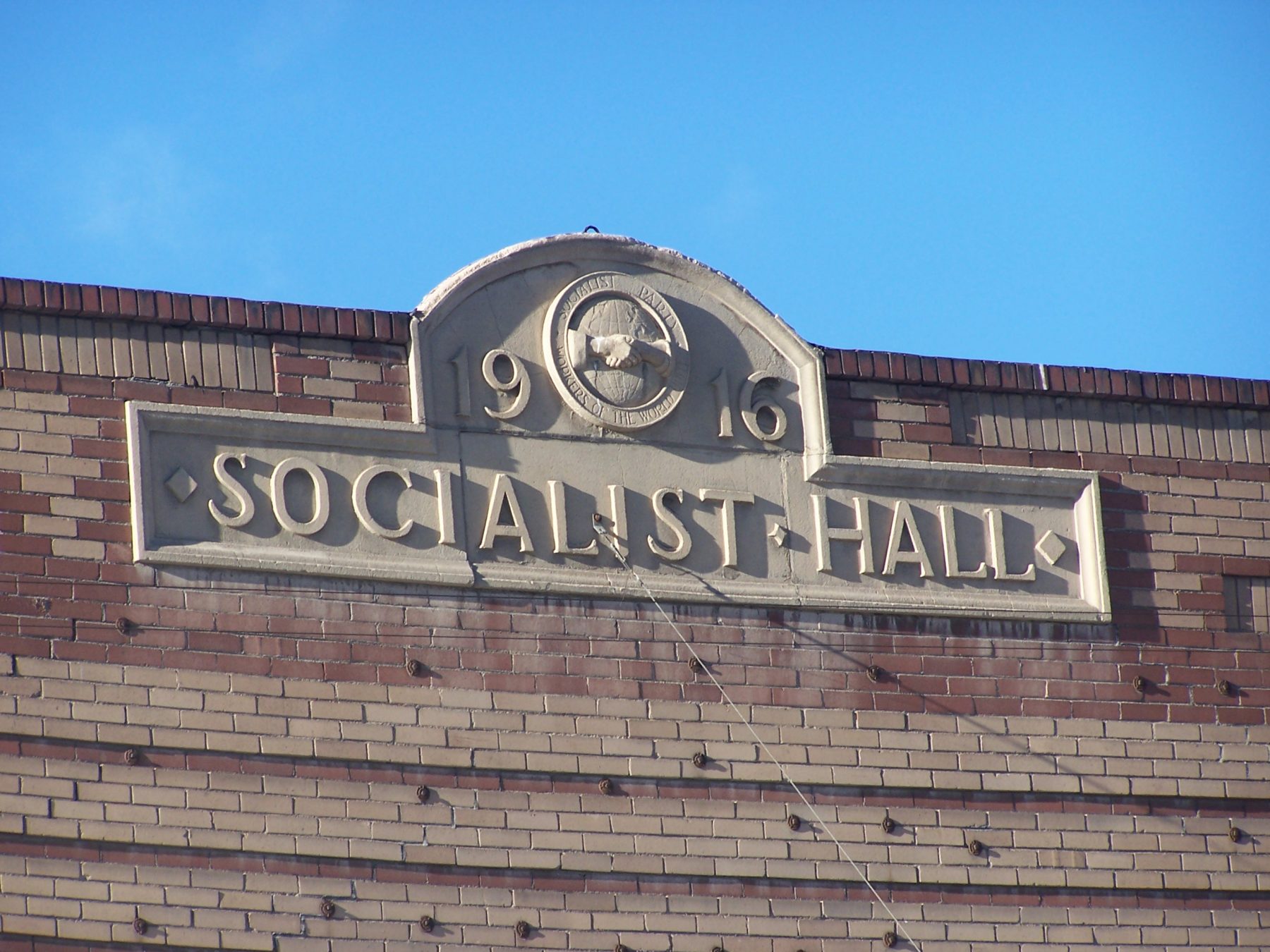

Taking after their German comrades, American socialists created, for a brief moment in the beginning of the 20th century, a working-class counterculture as well. Colorado miners, Oklahoma dirt farmers, Texas timber workers, and Indiana factory workers all read the same publications, listened to the same circuit lecturers, and cast their ballots for the same party on election day. These workers all paid their dues to the Socialist Party and carried their red membership card in their back pocket, but were united by more than that. The working-class culture permeated nearly every aspect of their lives. Socialists in thousands of towns across the US organized mass political education, created a left pole in the trade unions, started local socialist newspapers, formed worker co-operatives, and crucially, shot the breeze and drank beer together. The recognition of class exploitation brought people to the Socialist Party; the deep sense of camaraderie and shared struggle kept them there.

It is the job of every person who hopes for societal transformation to consciously create that working-class culture. It won’t happen on its own. Join DSA, support and sustain local socialist press like Red Fault, get together with other socialists in your union or organize a new union, organize neighborhood hangouts, and work toward creating hiking clubs, sports teams, and study groups for workers. Only through political organizing and building up workers’ organizations can we set our country on the path toward the transformation necessary to guarantee not only the bare necessities, but also the luxuries we deserve (including inexpensive beer!).

We want to hear from you. Do you have a workplace story or editorial you’d like to share with us? Email us at redfault@austindsa.org!